Looking deeper.

This text is written partially in response to a question posed to me at a recent talk about my artistic research into using human milk to paint: "Yes, but do you PAINT?" I quickly realized thatthe idea of PAINTING is still defined by the practice of pushing oil paint on stretched canvas and letting it set.

PAINT? With a genormous capital P? AND ONLY IN OIL?? YOU MEAN LIKE THIS?? I thought I WAS painting, all the time...is it not PAINTING when done in milk???

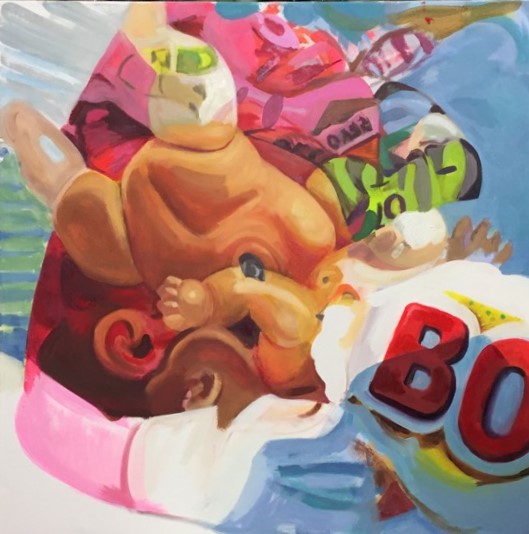

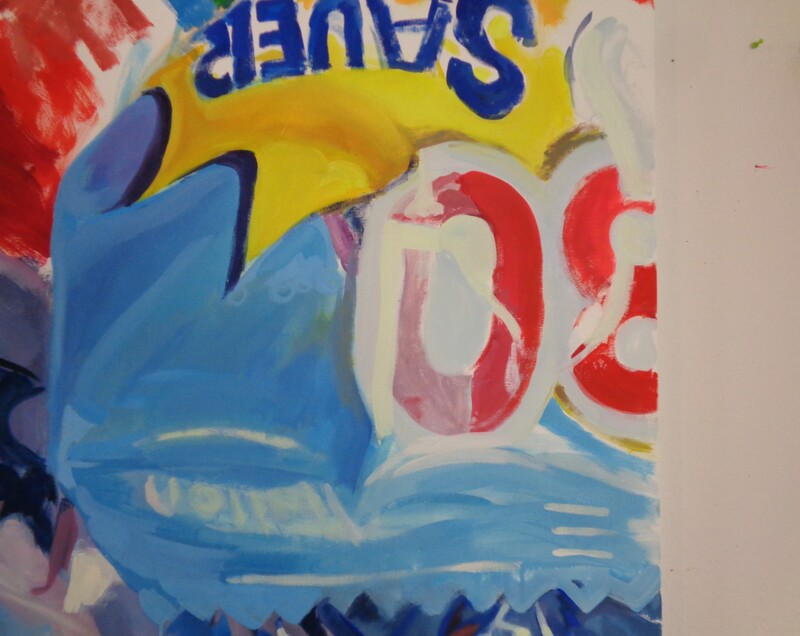

Weirdest doll in Weimar. 2014, 30 cm x 40 cm, oil on canvas.

Or like DER MALER, which I have not been able to find a full version of, where a super silly Ben Becker grunts and groans as he, in persiflage of our more romantic imagination of the PAIN of giving birth to a MASTERPIECE must look like for REAL PAINTERS? And would you have asked a German young GUY the same question?

Weirdest doll in Weimar. 2014, 30 cm x 40 cm, oil on canvas.

Or like DER MALER, which I have not been able to find a full version of, where a super silly Ben Becker grunts and groans as he, in persiflage of our more romantic imagination of the PAIN of giving birth to a MASTERPIECE must look like for REAL PAINTERS? And would you have asked a German young GUY the same question?

I studied painting in New York, at Purchase College and then Pratt Institute. Mostly our foundation classes were based on some version of the original Bauhaus introductory courses. One of my professors was fond of saying: „The way to paint is to paint. The way to start painting is to paint. There is no other way.“ He painted landscapes for his entire adult life, over forty years of green variations. I feel very lucky to have studied also with Irving Sandler, Judith Bernstein and Jane Dickson. I left New York City after being based there for 11 years, in early 2002. I had opened my first and last show in Manhattan on September 3rd, 2001 at Denise Bibro Gallery in 2001. Then I watched the scenery before my kitchen window in Brooklyn change, as the World Trade Center was erased, 8 days later. We could smell the cloud hovering over the cityscape for weeks, as we walked past photocopied images of people who had disappeared taped to the walls in the subway...Suddenly, the milk cartons had nationalist slogans on them: „United we Stand“.... and such. I left for Berlin. I felt pushed back into a predesigned space in a different way in Germany, perhaps because of my German passport. Or not?

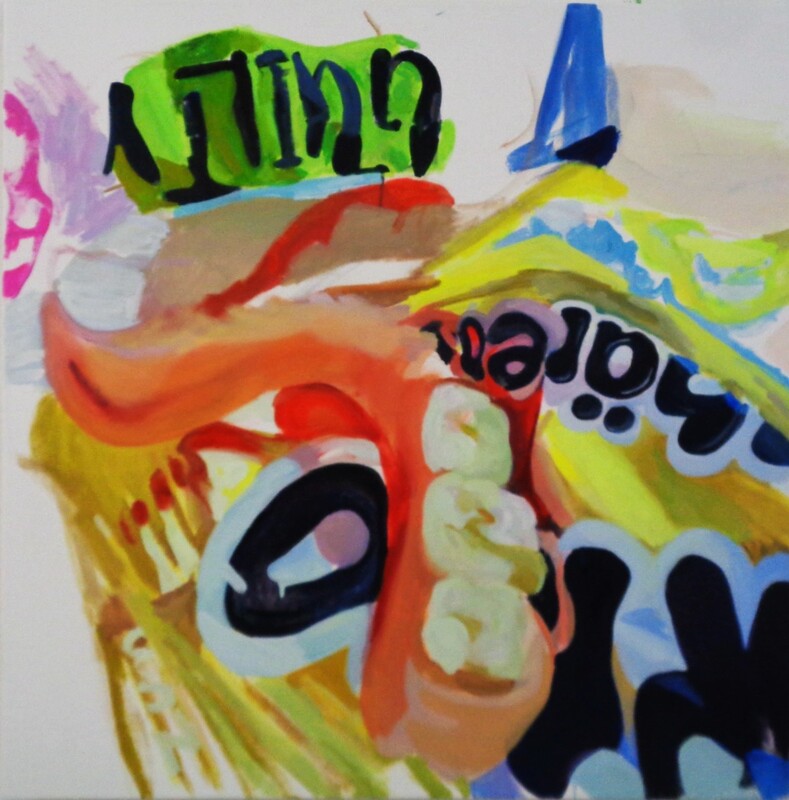

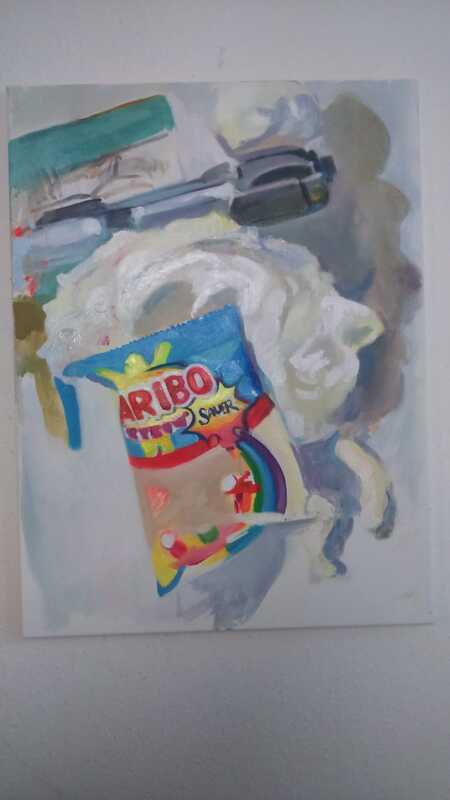

dolls, dolls, dolls (in Weimar) 80 x 60 cm, 2014

dolls, dolls, dolls (in Weimar) 2014 80 cm x 80 cm, oil on canvas.

Like so many of the students I later had the privilege to teach and mentor at Bauhaus-Universität Weimar, and the University of the Arts, Berlin, I had already had my doubts about a life plan based on the landscape painting professor, as much as I respected him. Forty years of green while the world was falling apart. I just couldn‘t do it.

Elkins describes the shock of the slow pace experienced by scholars encountering materiality in an artist studio work. He says:

"Art historians who are new to the studio can find their minds racing like the engines of cars stuck in ice.“

"Art historians who are new to the studio can find their minds racing like the engines of cars stuck in ice.“

„Slowness is painful. It follows that the experience causes anguish: nothing, it seems, is being learned, and no thought can find expression without being dragged through a purgatory of recalcitrant materials. Studio art can become a kind of chronic, low level pain, where the mind is continuously chafing against something it can not have. Academic thinking – the running equations, the scintillating conversations – aim to be as free of that pain as possible.“

Instead of striving as far away from this moment of academic frustration, it is as if we artists who looking for painting AND BEYOND were willfully placed ourselves in revisiting this moment of a mind racing while being stuck in ice and over again when we work as artistic researchers.

I founded my own artspace arttransponder.net with colleagues in Berlin in 2005 and funded projects that dealt with questions of participatory art at the interface to other disciplines until 2009, when I was hired to teach Public Art and New Artistic Strategies for 6 years at Bauhaus-Universität, Weimar.

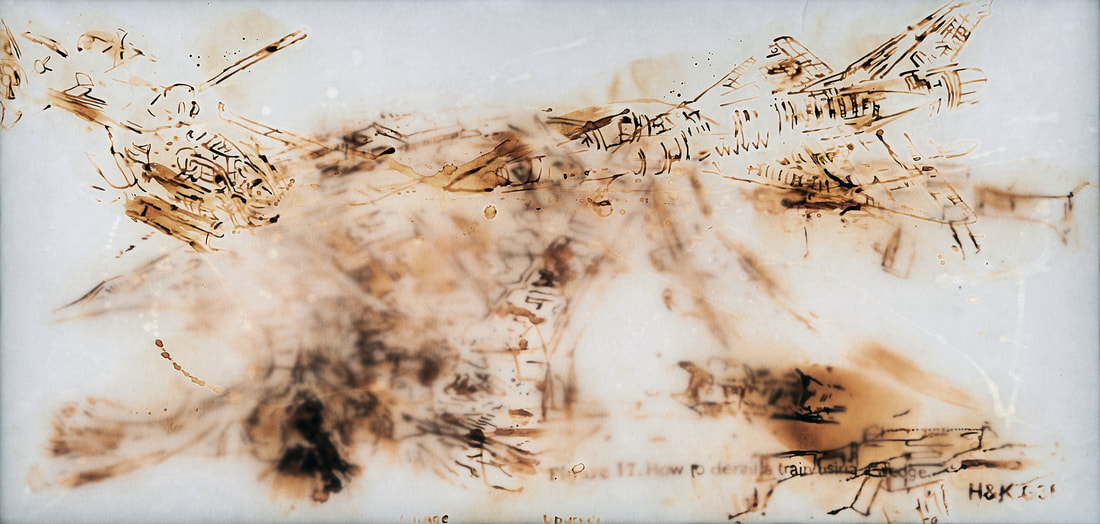

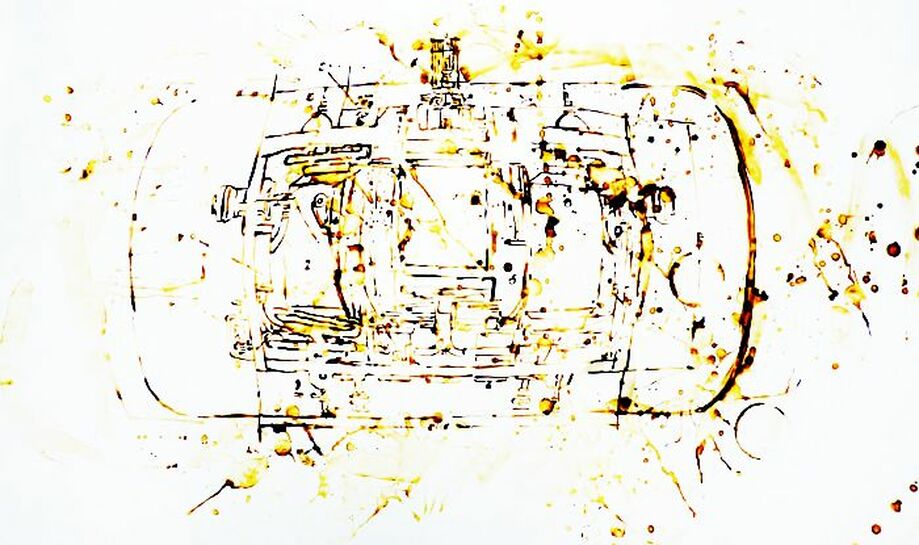

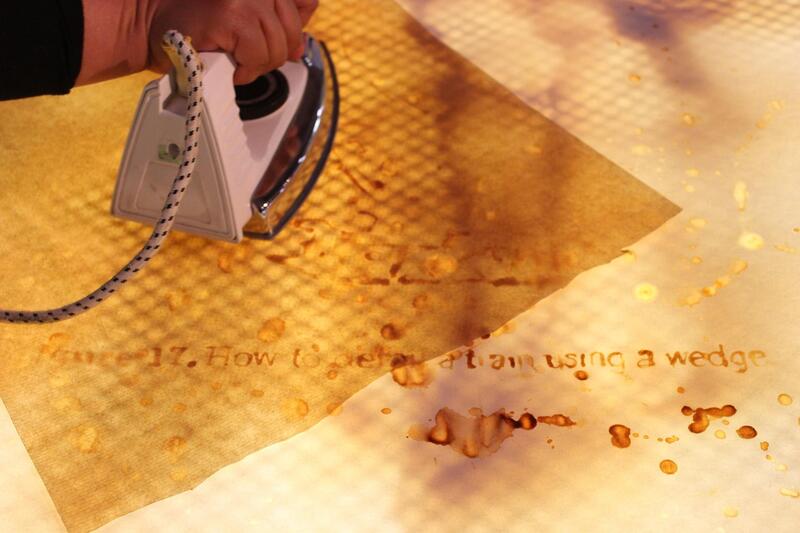

I began experimenting with human milk, making marks. I taught myself to paint in human milk.

This proved to be difficult and interesting (more here on painting in human milk).

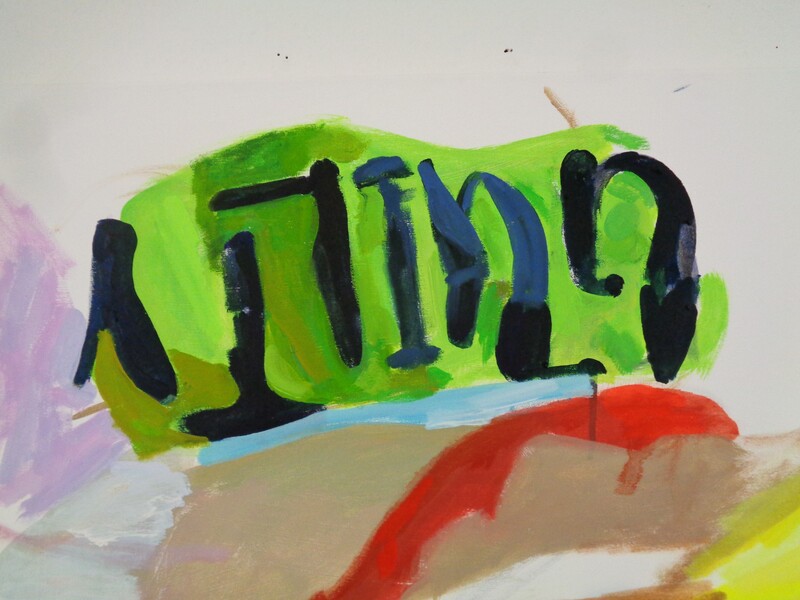

That question makes my ovaries screech. 2020. 240 cm x 180 cm handprinted in oil on canvas. Feldfünf, Berlin. Whocares festival.

In 2016, after serious illness I found myself lying flat on my belly, face down, for weeks at a time, immobilized. I began lcarving into linoleum. Linoleum became my new material infatuation. As material it has an equally "low" status in the visual arts as does human milk, but without the weirdness factor. It is usually associated with the production of crafty greeting cards. Basteln, done lovingly in privileged domestic contexts without being too stressed for time - an obviously gendered setting, not Gestaltung, not Design. I began experimenting with expansion and inks until I figured out how to print large format linoleum cuts in oil on canvas. I began exploring self-fictionalization, developing the a narrative around a central figure, Patricia Andersdottir Roth (Precarious Artistic Researcher), and first published and exhibited it in 2018, and then repeatedly, in Mexico and Germany. I was called to become a 50% Professor of Painting and Participatory Strategies with this work in 2021. I had the privilege of accompanying some amazing students in an exploration of painting combined with participatory strategies. BUT - only 50%. And despite the great atmosphere, 50% just did not cover costs: per hour pay way less than at public school. This remains a great job for those who can afford it.

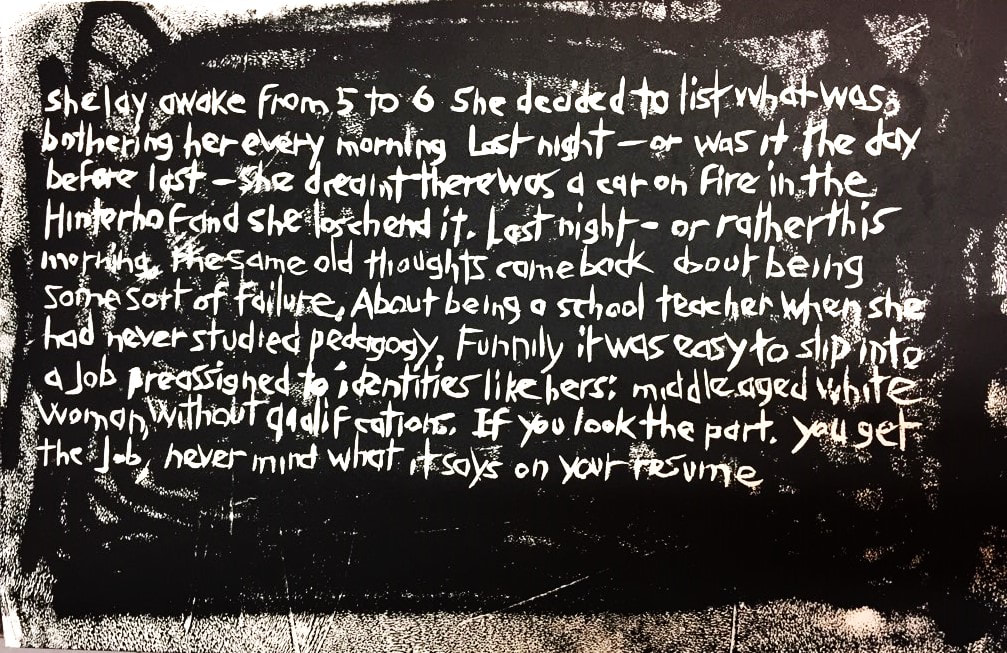

By then, Patricia Andersdottir Roth, (Precarious Artistic Researcher) was so destitute (She was looking for the Monument Against Patriarchy - MAP - when Precarity got in the Way.) and sick of forming work to apply for always too little funding while cultivating dependence on a better situated partner, (reality for many, many self described antibourgeois artists!!) she embarked on the wild ride that it was to convince the Berlin Senate, that, despite being a highly educated artist. she could teach in public schools. She also convinced them she could teach philosophy. She was asked: Aber was machst Du mit den schlechten Gedanken?

In 2016, after serious illness I found myself lying flat on my belly, face down, for weeks at a time, immobilized. I began lcarving into linoleum. Linoleum became my new material infatuation. As material it has an equally "low" status in the visual arts as does human milk, but without the weirdness factor. It is usually associated with the production of crafty greeting cards. Basteln, done lovingly in privileged domestic contexts without being too stressed for time - an obviously gendered setting, not Gestaltung, not Design. I began experimenting with expansion and inks until I figured out how to print large format linoleum cuts in oil on canvas. I began exploring self-fictionalization, developing the a narrative around a central figure, Patricia Andersdottir Roth (Precarious Artistic Researcher), and first published and exhibited it in 2018, and then repeatedly, in Mexico and Germany. I was called to become a 50% Professor of Painting and Participatory Strategies with this work in 2021. I had the privilege of accompanying some amazing students in an exploration of painting combined with participatory strategies. BUT - only 50%. And despite the great atmosphere, 50% just did not cover costs: per hour pay way less than at public school. This remains a great job for those who can afford it.

By then, Patricia Andersdottir Roth, (Precarious Artistic Researcher) was so destitute (She was looking for the Monument Against Patriarchy - MAP - when Precarity got in the Way.) and sick of forming work to apply for always too little funding while cultivating dependence on a better situated partner, (reality for many, many self described antibourgeois artists!!) she embarked on the wild ride that it was to convince the Berlin Senate, that, despite being a highly educated artist. she could teach in public schools. She also convinced them she could teach philosophy. She was asked: Aber was machst Du mit den schlechten Gedanken?

I got on the boat. The wagon? After completing 3 Masters degrees (MFA Painting, MS Art History, MA Art in Context) in 6 years and a PhD (in 5 years), and becoming a Professor of Painting, unbefristet but just 50%, I also, and in parallel, completed teacher education training (zweites Staatsexamen. School teaching pays substantially more than this 50% professorship at a private institution of higher education.) I submitted to normativity and became what I apparently looked like: an extremely hard working stereotypical German woman art teacher fulfilling all bureaucratic expectations on time by the book, killing off any last shred of desire to produce anything herself. No, I sorted my life as a single mother so that I could afford a continuous studio practice with which nobody would be able to interfere! I also found all the intense and draining interaction with about 100 students per week working part time (a lot of highly gendered care work!) fully satisfied my need for human interaction and participation and returned to painting for long stretches, all by myself, in my studio, working through the ideas and frustrations I developed for and experienced in teaching both in higher education and at school.

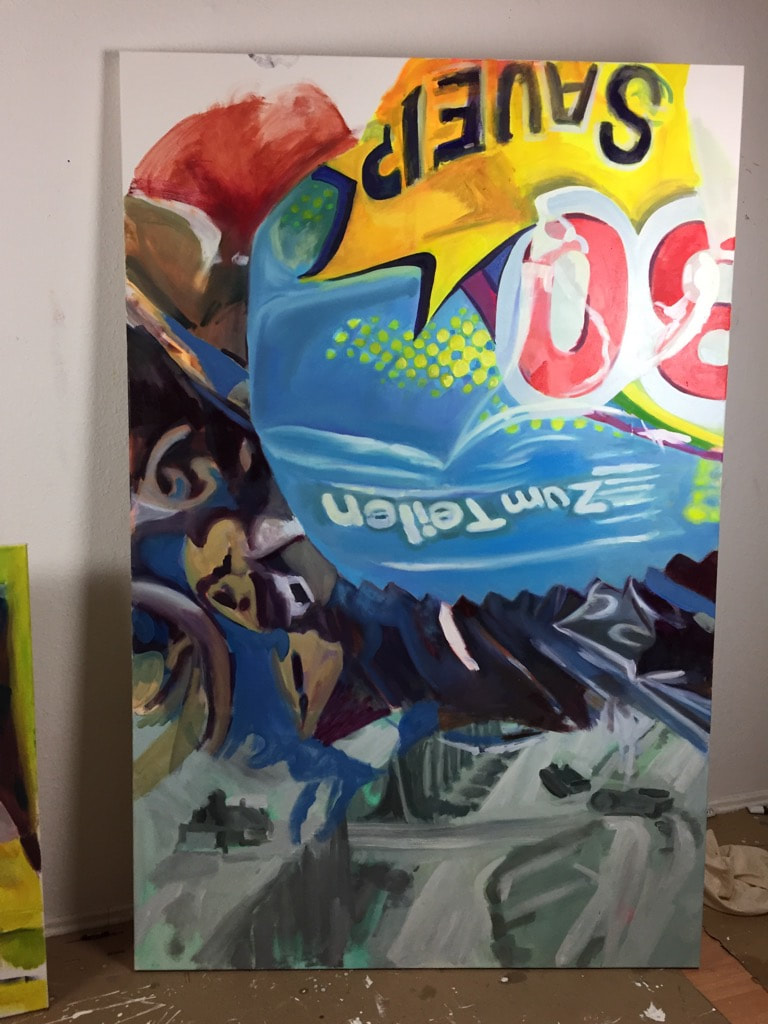

Almette (domestic warscapes), 40 x 40, 2016

Proudly powered by Weebly